Out of the tap, from a source

three hundred feet down, so close

I feel the shudder in the earth, water

spills over my hands, over the scallions

still bound in a bunch from the store.

I had thought to make salad, each element

cut to precision, tossed at random

in the turning bowl. Now I lay the knife

aside. I consider the scallions. I consider

the invisible field. Emptiness is bound

to bloom—the whole earth, a single flower.

—from Margaret Gibson’s “Making Salad”, after Eihei Dogen

Recently in Sewickley

A touch of tartan, a bit of burlap, and pops of paperwhites. From our house to yours, Merry Christmas!

Home is where the work is

Two weeks into the stay-at-home orders across the U.S., we moved to Pittsburgh. We’d planned the move months earlier. In the abstract, we’d been planning it for years. My husband, Peter, and I both grew up in western PA; this was our long-anticipated return. I called the moving company a few times to make sure we could still go. They seemed unfazed: the trucks were rolling; the movers would wear masks and gloves. It all turned out to be fine.

We moved into an apartment downtown, a short-term solution while we decided where to put down roots. Our space is small, but the windows look out over Point State Park, where Pittsburgh’s famous three rivers meet. During April, Mount Washington turned green. Even in the city, we have an expansive view of trees, and there’s a sense of being held by the hills around us.

We unpacked and dove back into the WFH-with-baby dance. We juggled conference calls, taking shifts at the desk in our bedroom, and jockeyed to claim the few leftover hours each day to get actual work done. This lasted about six weeks until we finally sat down and, sleep-deprived and struggling to keep up with work, accepted my mom and dad’s offer to help.

For most of May and all of June, we stayed with my parents, about an hour north of the city. I worked from the living room and Peter set up shop in the basement. My mom took care of our son each day – they picked flowers, read books, watched for ducks and frogs in the pond down the street.

We were so grateful for the extra hands, and I was reminded how healing certain places can be: the familiar breeze through the open windows upstairs, the sun-warmed brick patio outback, no small amount of Dairy Queen. By the end of our unexpected stay in my childhood home, we felt restored.

We returned to Pittsburgh in July and started our son at a new daycare. We settled into the apartment, the city, and a new rhythm – or at least a weird pandemic version of one.

Now it’s the end of August, and we’re in the process of buying the house that Peter grew up in. It's an outcome we'd hoped for: we’d only half-heartedly looked at other homes, and this one was built by his great-great-grandfather. The sentimentalist in both of us relishes the task of updating it for another generation.

We won’t move in right away – we want to make a few changes so that the house will suit the stage of life we’re at, a young family of three. This tracks with some of the work I do at Herman Miller, where, by applying a deep understanding of people and the processes they engage in at work, I get to play a small part in helping our customers create inspiring, effective workplaces that support exactly what they do each day.

Experts believe that one of the lasting impacts of the pandemic could be a cultural reset on how knowledge workers use the workplace – that, when the dust settles, we’ll land on a flexible balance of spending a few days each week at the office, connecting in-person with colleagues and the culture of our organizations, and the other few days working from home, getting individual work done, and reinvesting in our personal lives the time we save by not commuting to an office.

If this is what happens – and I think and hope it will – it’s not just going to impact workplace design. It will impact home design, too. So I’m especially inspired to focus the same strategies I use at work on our home renovation. For one thing, I want to carve out more spacious and intentional work areas than what our current footprint allows. But there are other things to consider, too: a wall we want to take down; the windows we’ll need to restore; the question of what to do with the beautiful but aging barn in the backyard. The decoration of this house takes on an almost spiritual dimension when I think of the ways we’ll live in it, and the impact, in turn, it will have on our lives.

This extended period in which many of us have had no choice but to spend more time at home has also made me want to dispense entirely with the notion that paying attention to how one arranges and designs a home is somehow frivolous, or merely decorative. Home is where we rest and nourish; it’s where we love and play. It’s no mere thing at all.

Meanwhile, within the constraints of our small apartment, Peter and I continue to refine how we work. His workspace – despite being squeezed into a hallway – has gotten a bit of a glow-up: dual monitors, a wireless keyboard, an Aeron chair. Not to be outdone, I’ve acquired an Eames molded plywood folding screen to stand between my desk and our bed – a much-needed physical boundary between work and life, and a less distracting background for video calls. From a well-being standpoint, we try to eat healthy, we have truly the best intentions for a regular home exercise routine, and our morning and evening walks to-and-from daycare add welcome structure to our days.

If you’d asked me a few months ago what to call these things, I’d have said that they’re best practices for working from home; a WFH toolkit, perhaps. But as the weeks pass, I’ve realized that they’re more than just that. They’re our essential tools for living – which lately has involved a great deal of work.

Originally published on LinkedIn on August 24, 2020.

Coveted

A night's stay in the High Meadow residences at Fallingwater.

Quoted

"It is approaching the magic hour before sunset when all things are related... "

—Walter Anderson

On repeat

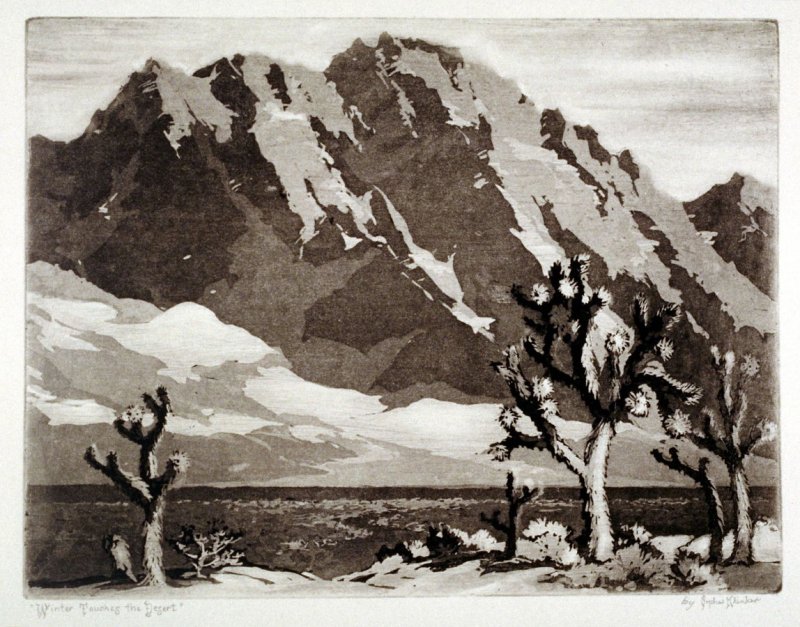

Today in Joshua Tree

Quoted

God has a way of making flowers grow.

He is both daring and direct about it.

If you know half the flowers that I know,

You do not doubt it.

He chooses some gray rock, austere and high,

For garden-plot, trafficks with sun and weather;

Then lifts an Indian paintbrush to the sky,

Half flame, half feather.

In desert places it is quite the same;

He delves at petal-plans, divinely, surely.

Until a bud too shy to have a name

Blossoms demurely.

He dares to sow the waste, to plow the rock.

Though Eden knew His beauty and His power,

He could not plant in it a yucca stalk,

A cactus flower.

—Sister Madeleva, "In Desert Places"

On repeat

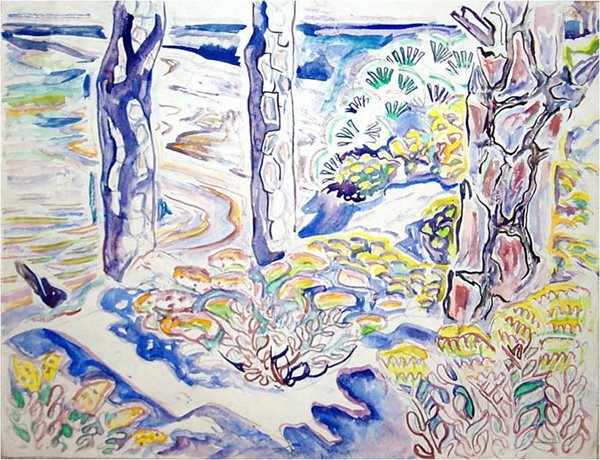

Muskoka in late July

On repeat

A few weeks ago in the Berkshires

On repeat

Last weekend in Big Sur

On repeat

Quoted

"There is no music, no worship, no love, when we take the world's wonders for granted."

—Rabbi Jules Harlow, There is No Singing without God: A Prayerbook for Shabbat, Festivals, and Weekdays

Yesterday at sunrise

On repeat

Recently for Apartment Therapy

A tour of Framebridge's Georgetown office.

Quoted

"Pick a flower on earth and you move the farthest star."

—Paul Dirac